Since the early 2000s, the “Diploma Divide[1]” has been under debate, and is a concept that some scholars argue was exacerbated by the 2016 presidential election. The “Diploma Divide” essentially describes a concept in which white voters who hold a college degree are more likely to vote for candidates who identify as members of the Democratic Party. Conversely, under this concept, white voters who lack a college degree are more likely to vote for the candidates who are members of the Republican Party. We can therefore ask: does this phenomenon also extend to racial/ethnic-minority voters? To answer this question, I collected data from various sources, the Cooperative Congressional Election Study[2], the Democracy Fund Voter Study Group[3], the Collaborative Multiracial Post-Election Survey[4], and the Data for Progress Covid-19 Response Weekly Tracking Poll[5]. I examined these sources because they collect pre- and post-election data over time, and they also collect demographic information – such as race/ethnicity and education – for each survey respondent. Please note that throughout this piece, lower levels of education range from no high school to a high school diploma. Higher levels of education are defined as some college up to a post-graduate university education. Based on my analysis, the results demonstrate that the Diploma Divide does not appear to extend to racial/ethnic-minority voters.

Does the Diploma Divide Exist for Racial and Ethnic Minorities?

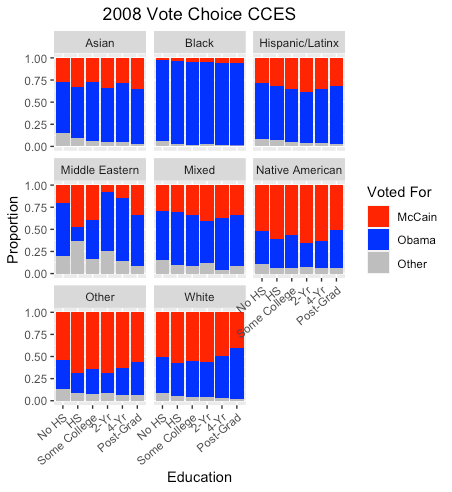

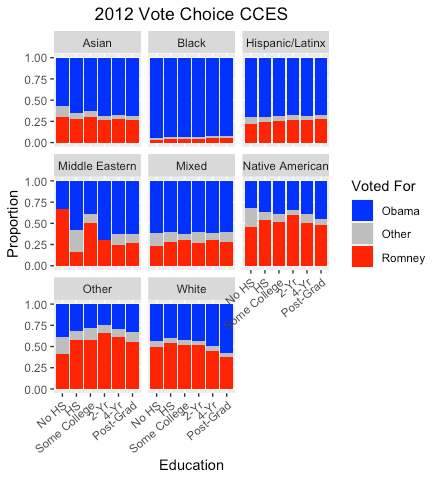

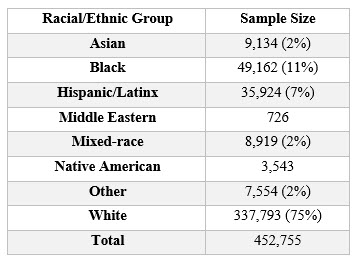

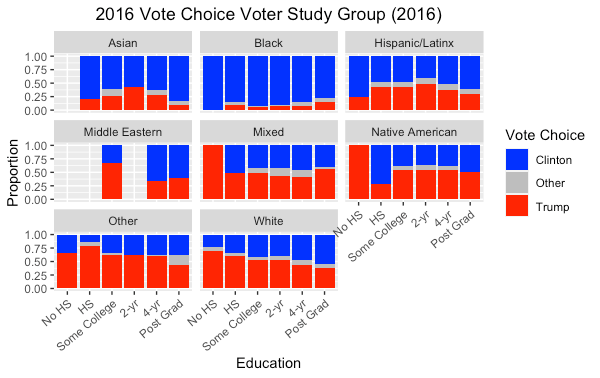

First, I drew upon data from the Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES). The data was collected in 2008, 2012, and 2016. In the table below I have listed the total sample size and proportions by race/ethnicity for each group. This data consists of 25% non-white and 75% white respondents, and thus may not be fully representative of minority groups due to the small sample size when compared to other surveys. Blacks more than any other minority group are significantly more likely to vote for Democratic candidates, regardless of their education level. Similarly, Asians and Hispanic/Latinx groups are also more likely to vote for Democratic candidates, regardless of education level. However, a small proportion of Asians and Hispanic/Latinx vote for Republican candidates. For both Middle Eastern and Mixed-race groups, there is more variation, but there does not appear to be a general trend in voter choice. Conversely, Native Americans are more likely than any other minority group to vote for Republican candidates, regardless of voter education. Members of minority groups that identify as “Other” (the survey report doesn’t define “Other” groups) are also likely to vote for Republican candidates, but there does not appear to be a general trend tied to education. People who identify as white and have lower levels of education tend to vote for Republican candidates, while more educated whites are more likely to vote for Democratic candidates. These results further confirm a “Diploma Divide.”

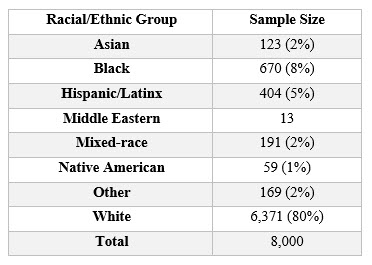

Second, I drew upon data from the Democracy Fund Voter Study Group, using data that was collected in 2016. In the table below I have listed the total sample size and proportions by race/ethnicity for each group. This data consists of 20% non-white and 80% white respondents, and thus may not be fully representative of minority groups due to the small sample size in comparison to other surveys. Blacks more than any other minority group are significantly more likely to vote for Democratic candidates, regardless of education levels. Similarly, Asians and Hispanic/Latinx groups are also more likely to vote for Democratic candidates, regardless of education level. Although, a small proportion of Asians and Hispanic/Latinx who vote for Republican candidates. For both Middle Eastern and Mixed-race groups, there is more variation, but there does not appear to be a general trend for vote choice. Conversely, Native Americans are more likely than any other minority group to vote for Republican candidates, regardless of education. Members of minority groups that identify as “Other” (the survey report doesn’t necessarily define “Other” groups) are also likely to vote for Republican candidates, but there does not appear to be a general trend tied to education. Similar to the previous analysis, people who identify as white and have lower levels of education tend to vote for Republican candidates, while more educated whites are more likely to vote for Democratic candidates. These results further corroborate what we know about the “Diploma Divide.”

What Does Other Data Say?

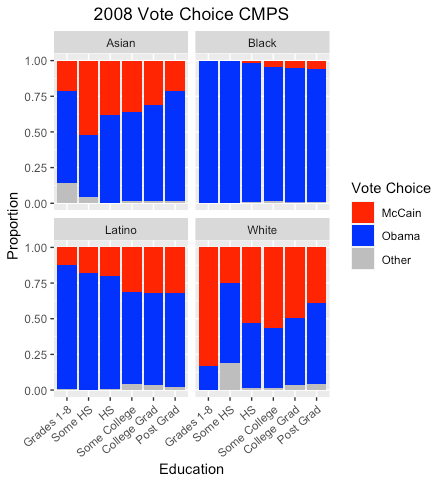

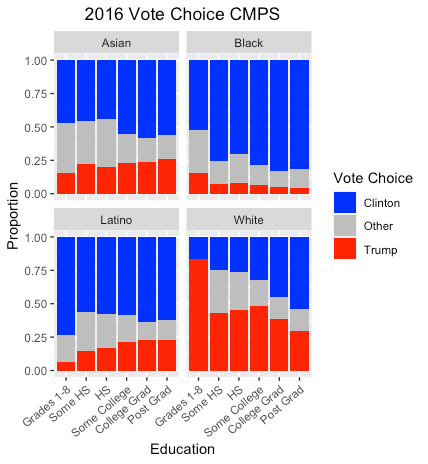

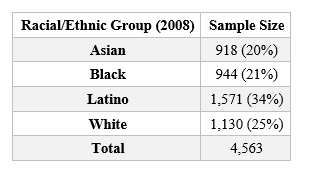

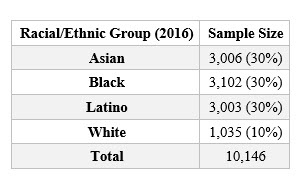

Additionally, I drew upon data from the Collaborative Multiracial Post-Election Survey (CMPS), using data collected in 2008 and 2016. In the table below, I have listed the total sample size and proportions by race/ethnicity for each group. The data for 2016 consists of 90% non-white and 10% white respondents, and the data for 2008 consists of 75% non-white and 25% white respondents. Thus, in comparison to the other surveys I analyzed, both of these surveys are more representative of racial/ethnic-minority groups due to oversampling. Similar to previous trends I found in the other surveys, Black people more than people of any other minority group are more likely to vote for Democratic candidates, regardless of education level, although there is slight variation in the 2016 election. With some variation, Asians are also likely to vote for Democratic candidates, even after accounting for education. Similarly, Latinos are also likely to vote for Democratic candidates. However, it appears the more educated Latinos are more likely to vote Republican candidates in comparison to their less educated counterparts, which could potentially suggest an inverse trend of the “Diploma Divide.” Conversely, the opposite relationship is seen for white people, the less educated they are, the more likely they are to vote for Republicans and vice versa.

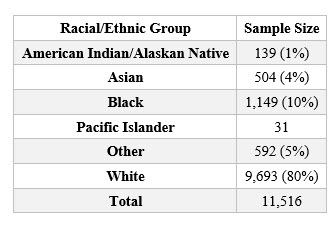

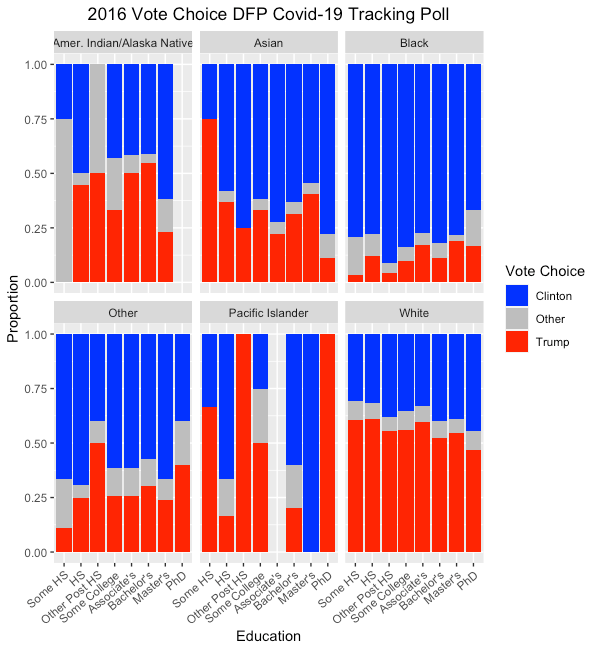

Lastly, I drew upon data from the DFP Covid-19 Response Weekly Tracking Poll, and used data that was collected in 2020. This data consists of 20% non-white and 80% white respondents, and again, thus may not be fully representative of minority groups due to the small sample size when compared to other surveys. Similar to previous trends I found in the other surveys, Black people are more likely to vote for a Democratic candidate, regardless of education level. There is more variation for American Indian/Alaska Natives, with the less well-educated voting for other candidates, and the more well-educated voting for Democrats. Asians are more likely to vote for a Republican candidate on the basis of education, and vice versa, thus potentially suggesting a “Diploma Divide.” There is more variation for Pacific Islanders, with some voting Republican and others voting Democratic, but this trend does not appear to be tied to education levels. Those that identify as “Other” (this survey doesn’t necessarily define potential groups) are more likely to vote for Democratic candidates, regardless of their education level. Lastly, whites in this data source are more likely to vote for Republican candidates. It is difficult to see a “Diploma Divide” that is apparent for whites in the other survey data.

I am grateful to Dr. Matt Grossmann for his contribution to this project and his feedback. I am also grateful to IPPSR for giving me the opportunity to conduct this research. My own work has examined state legislative candidates with working-class backgrounds, such as those who have held blue-collar jobs in the past. Through this work on the “Diploma Divide” I have been able to analyze respondents of different racial and ethnic backgrounds with varying education levels. Overall, my research suggests there are gender divides among voter preferences, indicating that there is a “Diploma Divide”[6]. For example, roughly 70% of non-college educated white men voted for President Donald Trump, the Republican candidate, in the 2020 election. Thus, future research should examine whether potential gender divides exist for members of racial/ethnic-minority groups.

Erika Vallejo is a graduate policy fellow at IPPSR. She is a second-year doctoral student at MSU studying American politics and public policy. Her primary research interests are race, ethnicity, gender, class and labor policy.

Sources

Ansolabehere, Stephen, 2010, "CCES, Common Content, 2008", https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/YUYIVB, Harvard Dataverse, V6, UNF:5:7eeaUMPVCcKDNxK6/kd37w== [fileUNF]

Ansolabehere, Stephen; Schaffner, Brian, 2013, "CCES Common Content, 2012", https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/HQEVPK, Harvard Dataverse, V9, UNF:5:Eg5SQysFZaPiXc8tEbmmRA== [fileUNF]

Ansolabehere, Stephen; Schaffner, Brian F., 2017, "CCES Common Content, 2016", https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/GDF6Z0, Harvard Dataverse, V4, UNF:6:WhtR8dNtMzReHC295hA4cg== [fileUNF]

Barreto, Matt A., Frasure-Yokley, Lorrie, Hancock, Ange-Marie, Manzano, Sylvia, Ramakrishnan, S. Karthick (Subramanian Karthick), Ramirez, Ricardo, … Wong, Janelle. Collaborative Multi-racial Post-election Survey (CMPS), 2008. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2014-08-21. https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR35163.v1

Barreto, Matt, Lorrie Frasure-Yokley, Edward D. Vargas and Janelle Wong. 2017. The Collaborative Multiracial Postelection Survey (CMPS), 2016. Los Angeles, CA.

Democracy Fund Voter Study Group. VIEWS OF THE ELECTORATE RESEARCH SURVEY, December 2016. [Computer File] Release 1: August 28, 2017. Washington DC: Democracy Fund Voter Study Group [producer] https://www.voterstudygroup.org/.

Schaffner, Brian, 2020, "DFP Covid-19 Response Weekly Tracking Poll", https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/XJLZIN, Harvard Dataverse, V9, UNF:6:GT9HCj1G03muDJiDgkXU0Q== [fileUNF]

[1] https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2018/11/education-gap-explains-american-politics/575113/