The capacity and skill to connect digitally are critical in the 21st Century economy. Inequalities in broadband connectivity and access devices, often referred to as the “homework gap,” are one major obstacle to connecting our human capital with the technologies – and the goods and services – of the future. The pandemic coronavirus of our present makes these dynamics all the more compelling. A recent study by the Quello Center in collaboration with Merit Network and several Michigan intermediate school districts examined data from 3,258 students, aged 13 and older, in 173 grade 8-11 classrooms. The report paints a detailed picture of the direct and indirect effects of insufficient Internet connectivity on young learners and their potentially lifelong repercussions. Only 47% of students who lived in rural areas had high-speed Internet access, compared to 70% in towns and 77% in suburban areas. Both lack of broadband infrastructure and socio-economic factors contributed to these varying adoption rates.

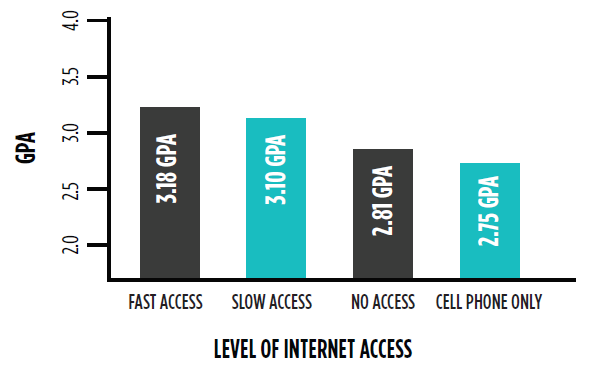

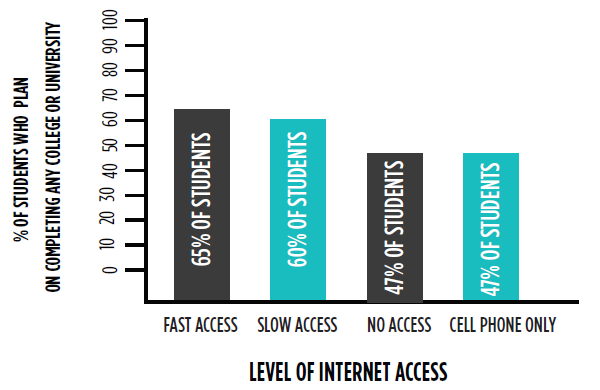

Internet access supports homework completion and affects digital skills, which in turn affect educational outcomes. Controlling for socio-economic and other factors, students without high-speed Internet access at home had lower grades and lower digital skills. They also were less likely to pursue a college or university education or STEM-related careers. In contrast, students with fast Internet access had substantially higher digital skills, which were associated with higher scores on SAT, PSAT 10 and PSAT 8/9 tests. Students who were dependent on cellphones only to access the Internet are comparable to students with no Internet access.

|

|

|

Disparities in broadband access to remote and otherwise disadvantaged locations are not a new problem. That they persist is an outcome of several factors, including the cost of broadband, the failure of public policy to adopt workable solutions to overcome market deficiencies, and stakeholder interests that often block innovative solutions. Large service providers have only weak interest in deploying fast broadband to remote areas and disadvantaged populations. Moreover, individual subscribers may not fully appreciate the benefits of broadband, further increasing the gap between their willingness to pay and the cost of deploying broadband.

COVID-19 most likely has changed these perceptions and increased the willingness to pay for fast connectivity. Many stakeholders have responded with measures that can alleviate immediate constraints. Schools have sought to overcome broadband access barriers by distributing tablets, wireless hotspots, and sometimes deploying connectivity infrastructure. Network operators have responded by expanding low-income programs such as Comcast’s Internet Essentials, waived data caps on mobile data plans, and offered discounted mobile hotspot plans. The federal government has provided support for many of these initiatives in the CARES Act and possibly in additional appropriations authorized by U.S. Congress.

Decentralized entrepreneurship and initiative certainly have mitigated the impact of the pandemic, but sustainable solutions require more. Correcting the underlying market deficiencies also requires support from good policy and leadership at the local, state and federal level. Federal subsidy programs, such as the E-Rate and Lifeline programs, need to be reformed to support broadband more effectively. Connect America programs must be based on reliable data rather than the existing erroneous broadband map. The $20.4 billion Rural Digital Opportunities Fund (RDOF) program is an important measure. Similar programs are needed for urban areas with high concentrations of unserved households.

Michigan would benefit from better coordination of broadband policy at the state level and from state-level funding programs. Already in 2016, key elements of a state-wide plan were developed in Michigan but never implemented. The state and local communities could support broadband development by removing obstacles to private and public entrepreneurship. Appropriate planning and coordination between different infrastructure projects, such as dig-once policies could reduce deployment costs greatly. Finally, there is role for decentralized bottom-up initiatives to increase digital inclusion and digital literacy. Innovation and collaboration can build a resilient K-12 education ecosystem that will be able to weather future disruptions.

References

Hampton, K., Fernandez, L., Robertson, C., & Bauer, J. M. (2020). Broadband and student performance gaps. Quello Center Report, Michigan State University. Available at https://quello.msu.edu/broadbandgap and SSRN: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3614074.

Bauer, J. M., Hampton, K. N., Fernandez, Z., & Robertson, C. T. (2020). Overcoming Michigan’s homework gap: The role of broadband Internet connectivity for student success and career outlooks. Quello Center Working Paper No. 06-20. Available at https://quello.msu.edu/broadbandgap.

Johannes M. Bauer was appointed Quello Chair for Media and Information Policy and the Director of the Quello Center in August 2018. He was trained as an engineer and economist, holding master’s and doctoral degrees in economics from the Vienna University of Economics and Business Administration, Austria. Much of his research centers on policy issues critical to the Quello Center, such as the design of policy and regulation for advanced media and the Internet, cybersecurity, innovation in the digital economy, and measures to increase digital inclusion.

He and his team of Quello Center researchers are winners of an IPPSR Michigan Applied Public Policy Research Program award resulting in an IPPSR MAPPR paper presenting exhaustive research and insights into broadband access and educational success in Michigan.